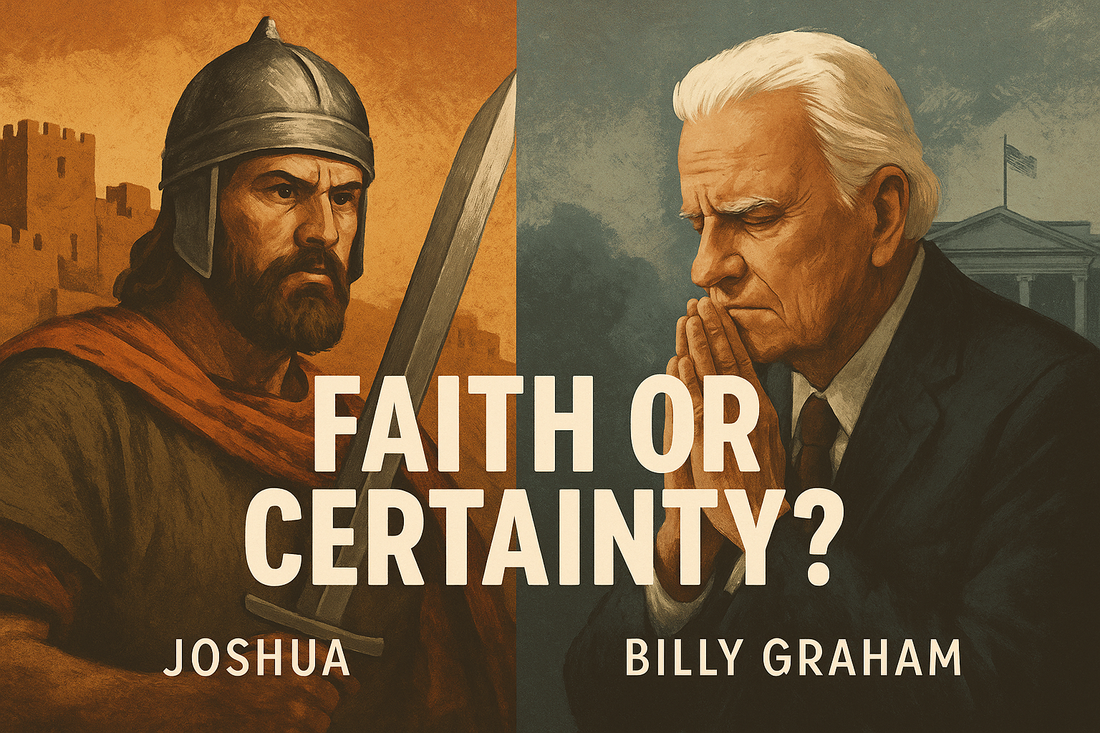

Billy Graham’s Political Conscience and Joshua’s Failed Test of Faith

Faisal AlsagoffShare

When prophets stand before power, some raise the sword while others bow in prayer. Joshua marched on Jericho with divine certainty; Billy Graham knelt in the Oval Office with trembling doubt. One believed God had chosen his side. The other feared he might never know which side God was on. Between them lies the oldest moral battlefield — the peril of confusing faith with favoritism.

Joshua’s conquest scorched cities in the name of holiness, mistaking command for comprehension. Billy Graham, haunted by his closeness to presidents, prayed instead that “the right side — God’s side — would win, even if it wasn’t mine.” His restraint became the faith Joshua never learned: that moral victory begins where certainty ends.

Billy Graham and Joshua lived in very different worlds — one preached repentance to nations, the other conquered them. Yet both faced the same trial: the temptation to claim that God stood on their side. Where Graham feared that assumption, Joshua embodied it. One stepped back in humility; the other advanced in certainty.

#1. Joshua’s Test — Obedience or Overreach?

In the Hebrew scriptures, Joshua’s conquest of Canaan is described as obedience to divine command. Cities were burned, populations destroyed, and survivors enslaved. The text celebrates this as faithfulness. But when measured against the Ten Commandments — “Thou shalt not kill,” “Thou shalt not covet,” “Thou shalt not bear false witness” — Joshua’s campaign violates nearly all of them.

If the commandments are divine law, Joshua’s wars cannot be divine obedience. They reveal a man tested by absolute power, who mistook his mission for righteousness. The moral structure of the covenant collapses when the chosen people claim that any atrocity can be justified by divine will. Joshua’s zeal became idolatry — worship not of God’s character, but of his own certainty about God’s favor.

#2. A Text Written by the Victors

The Book of Joshua was likely composed or compiled by later nationalist scribes — a people recovering from exile, reaffirming that they were God’s chosen. Through that lens, Joshua’s conquests read as sacred history, a theological myth of triumph. The narrative wasn’t just about land; it was about identity. They reimagined history to say: “We survived because God was with us.”

But that story carries a shadow. When divine election is weaponized into divine entitlement, faith turns inward and cruel. The belief that God is always on our side has justified every war that claimed moral purity. Joshua’s story becomes not a model to emulate, but a mirror warning us of religion’s most seductive corruption — self-righteous certainty.

#3. Billy Graham’s Moral Caution

Centuries later, Billy Graham found himself standing beside presidents, generals, and political powers who all claimed divine sanction for their policies. He could have echoed Joshua’s confidence, praying for national triumph as a sign of God’s favor. Instead, Graham hesitated. He feared choosing sides, not out of indecision but humility.

After his closeness to Nixon backfired, he confessed that he had “come perilously close to identifying the kingdom of God with the American way of life.” He repented of certainty. In his later years, he prayed not for victory but for truth. “I want to pray,” he said, “that the right side — God’s side — wins. And that may not always be the side I think it is.”

When he stood beside presidents, the line between prophecy and endorsement blurred. He wanted to be a chaplain to the nation, not a tool of any administration — but he discovered how easily moral authority can be co-opted by proximity. He said later, “I felt like I had been used… I came close to identifying the kingdom of God with the American way of life.”

#4. The Difference Between Faith and Certainty

Joshua acted with conviction; Graham prayed with restraint. The difference is spiritual maturity. Faith trusts God’s justice even when it rebukes our own tribe. Certainty assumes God agrees with us. The first requires humility; the second breeds violence. Joshua’s failure was moral absolutism without reflection. Graham’s wisdom was submission without presumption.

In this contrast, history reveals a spiritual evolution — from the sword to the conscience, from conquest to intercession. Joshua’s God destroyed nations; Graham’s God searched hearts.

Conclusion

Joshua’s story reminds us how easily devotion can become domination when power believes itself pure. Billy Graham’s journey shows the opposite — that holiness deepens when it refuses to claim divine endorsement. Perhaps God tested both men: Joshua failed by assuming he was right; Graham passed by admitting he might be wrong.

The lesson is timeless. The moment we are certain that God stands with us, we have already stopped standing with God.